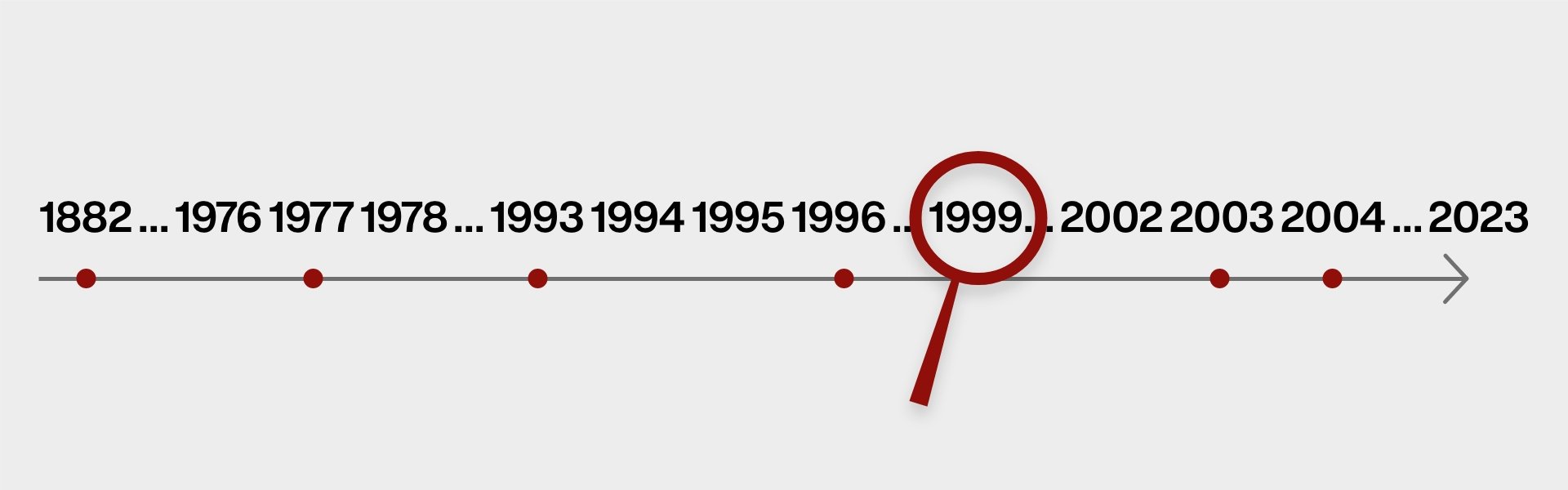

Regulations for drinking water hygiene: a historical summary

Drinking water is essential for life itself. However, if pathogens like Legionella get into our drinking water, then these can become a serious risk to human health. To prevent this from happening, the drinking water quality in buildings is now subject to strict regulations. And this legislation has a long history. The following blog post provides you with an overview of the milestones in drinking water hygiene legislation from the 1970s to the present day.

The DVGW as a pioneer in Legionella prophylaxis

Unlike Pseudomonas aeruginosa (cf. DVGW W 551-4, discovered circa 1882), Legionella is a comparatively new problem: the first known Legionella outbreak took place in the USA in 1976, with Legionella first being identifiable in culture since 1977. Another few years then passed until the causes could be properly determined.As it transpired, Legionella outbreaks are attributable to systems carrying water, which means that specific recommendations for action could then be drawn up. In so doing, the DVGW established the reputation it retains today as a publisher of best practice on maintaining drinking water hygiene in buildings. The first related technical code was published as DVGW W 551 in 1993. This applied to new buildings only and was supplemented by DVGW W 552 for renovation projects in 1996. In April 2004, both worksheets were then combined and remain valid to the present day as DVGW W 551, in the edition 04/2004. The worksheet is currently being revised.

25 years ago: VDI 6023 enters into force

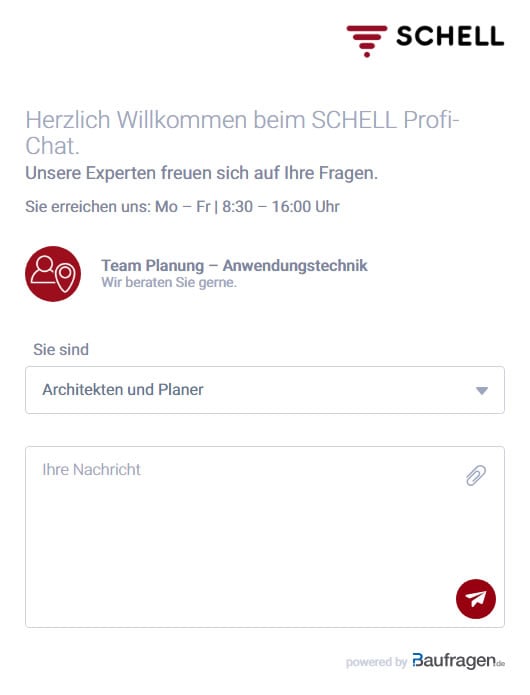

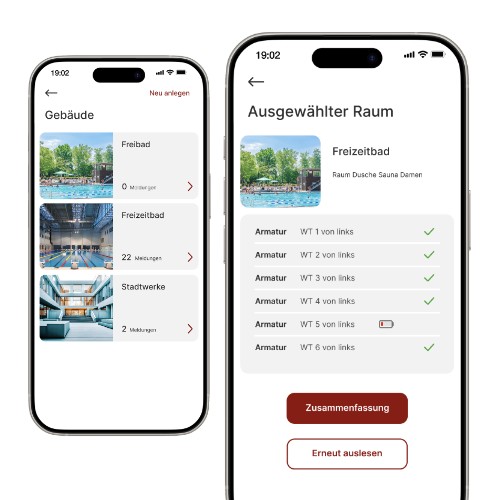

At the behest (and with the support) of the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA), the VDI published the approved version of VDI 6023, entitled ‘Hygiene-aware planning, execution, operation and maintenance of drinking water systems’ in December 1999. Its authors included leading hygiene experts and industry specialists. As a compendium of drinking water hygiene, VDI 6023 has long functioned as a generally accepted code of practice for hygiene, although it was not intended to (nor indeed can) replace the DIN standards for the planning and installation of drinking water installations. Nonetheless, it does summarise some key aspects of relevance for hygiene, which could not be explained at this level of detail in the DIN 806 and 1988 series or in DIN 1717. Furthermore, it was the first code of practice that specified the need to complete a full exchange of water across all tapping points after no more than 72 hours. This core requirement remains valid even today. Building operators may carry out the required exchange of water either manually or as an automated task – e.g. with highly efficient water management systems.

The first legislation appears in 2003: monitoring drinking water quality in buildings

In 2002, SCHELL’s hygiene specialist Dr Peter Arens published his first technical article in the IKZ journal, entitled ‘Hygiene aspects in the design and operation of drinking water installations, Part 1: Impairments to drinking water hygiene’ and ‘Part 2: Examples from practice’. At the time, operators of drinking water installations were not legally required to conduct building inspections. Since then, the industry is much better informed. The starting point for this was the 2001 German Drinking Water Regulation (TrinkwV), which entered into force at the start of 2003. This law was the first to require inspections at the tapping points of drinking water installations. Building operators were now required to have their drinking water tested either on an ad hoc basis or as required by the local authority. Public health offices were also tasked with carrying out spot checks of drinking water to identify “Legionella in central heating systems connected to the plumbing system that are used to supply water to the general public...” – e.g. in schools, nursery schools, hospitals, hospitality sector buildings and other community facilities. As insights on maintaining water quality in buildings were acquired step by step, these were used as the basis for the continual development of the following drinking water legislation as well as the technical solutions offered by manufacturers. With one TrinkwV amendment then defining the ‘point of compliance’, a responsibility for ensuring the high quality of water supplied to each tapping point was also imposed on building operators, fit-out planners and tradespersons.

A further milestone: 2004 Expert Consultation in Bonn

Another important milestone for drinking water hygiene in buildings can be dated precisely. Namely to 31 March 2004, the date when Professor Martin Exner invited experts to attend a consultation at the University of Bonn Medical School. At this event, “plumbing systems used to supply water to the general public” were designated a “potential reservoir for infection.” As Prof. Exner went on to say: “Certainly, a proactive strategy is the only proper approach here, in contrast to a reactive strategy.” The findings from this consultation were published in the German Federal Health Gazette (V. 49, pp. 681–686) in 2006. This day marks the beginning (or the affirmation) of many new technical developments in the industry.

2011 TrinkwV: Legionella as a routine parameter

In 2011, a TrinkwV amendment (section 14(3)) added a new duty for operators of water supply systems by requiring them to carry out periodic testing for Legionella and also introduced a new technical term, ‘hazard analysis’, which involves testing to determine “compliance with generally accepted codes of practice as a minimum requirement.” These hazard analyses (known as risk appraisals since 2023) provided a way to critically assess the current condition of the installation systems and to an extent also led to a re-evaluation of contemporary installation practice.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/b/csm_symstemloesungen_e2_thumb_6bca267f26.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/user_upload/images/menu/menu_service_downloads_broschueren.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/7/csm_menu_unternehmen_ueber-schell_awards_f6cec25b1d.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/0/csm_menu_unternehmen_ueber-schell_wasser-sparen_41036d2dd9.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/user_upload/blog/2024/historie_trinkwasserhygiene/50_Jahre_Trinkwasservordnung.jpg)